Ana Torfs, Approximations/Contradictions

Launch date: December 2, 2004, Artist Web Projects

Overview

For Approximations/Contradictions, Belgian artist Ana Torfs focuses on the Hollywood Songbook, a collection of very brief, powerful songs written by the German-Austrian composer Hanns Eisler in 1942 and 1943 while he was in exile in California. She elicited powerful performances from a group of very talented, diverse people singing the songs, and weaves them together into something entertaining and beautiful yet deeply disturbing and compelling.

In 2019, this project was reprogrammed in HTML5 because Flash is no longer supported by most browsers. The initial Flash version can be viewed here.

The recent work of the young Belgian artist Ana Torfs includes several slide projection installations, series of photographs and prints, a video installation, a feature-length film, and various publications. Through certain figures, seemingly selected at random from Western History (Beethoven in her feature film Zyklus von Kleinigkeiten1, Joan of Arc in the slide projection installation, Du Mentir-Faux2), Torfs opens the door for new investigations and perceptions of the past. An essay about Torfs' work, Impossible Portraits,3 asks how much or how little can be read in an image of a face, or "Is it possible to contain a truth within a portrait of the person portrayed?" Joined with this is an examination of the relationship and tension between text and image, between reading and visualizing.

For Approximations/Contradictions, Torfs casted 21 performers of various origins4, most of them living in Belgium, to each sing one song from theHollywood Songbook, a collection of 49 songs for piano and one voice by the German-Austrian composer Hanns Eisler, written in 1942-43 while he was in exile in California. The lyrics of the 21 pieces she chose to include, which concentrate on themes of war, exile, and Hollywood, were written by Eisler's frequent collaborator, Bertolt Brecht. Torfs asked the performers to make a list of the songs they most preferred to sing, then she assigned one song to each person in consultation with them.

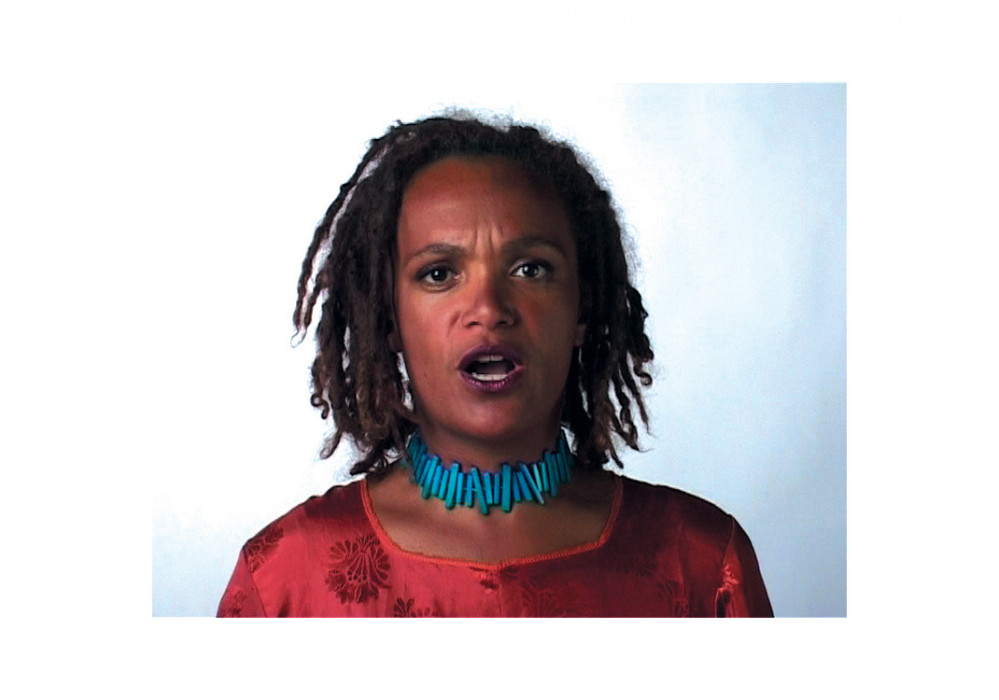

Interested in responding to the setting in which people typically view the web, Torfs wanted to offer a kind of intimate cinema. Playing off the convention of cast credits at the end of films, three versions of each song are offered from the project's main page, with song titles in the position of the role. The first version (linked to each performer's name) shows each one mentally singing the song while listening to the piano. During the rehearsals for the project, Torfs discovered that every singer very quickly "acted" the song in a very specific way. For the second, (accessible by clicking the line connecting the name to song title) Torfs asked the singer to be conscious of this and to repeat it. This version also presents Piet Kuijken, the talented young pianist whose face tells as much as his interpretation of the music. For the third version (linked to each song title), Torfs asked the performers to gaze directly into the camera, and asked them to wear something they felt was appropriate to the subject of their song, as if they were being filmed for a musical. Contrary to the first versions where everyone is dressed in a neutral white, in this final one, the women wore makeup and their hair-styles often varied dramatically.

She filmed the performers in close-up, framing them in a style consistent with a portrait: a bust with a little headroom, cropped mid-chest, with a white background. Her professional training as a filmmaker quickly becomes evident - the quality of the footage is impressive, with the camera's focus and the audio recording so precise that the subjects, as well as their voices, feel eerily present. Yet these three different renditions (Approximations) have extremely varied impacts. Watching the first, devoid of language as in a silent movie, one can sense the performer's concentration, singing even while mute. English translations of the original German lyrics accompany the second and third versions. The second version feels, as the first did, slightly voyeuristic, watching the performers sing in a very personal style. And in the third version, with the singer gazing directly at the camera, the viewer is intensely engaged by the performer's metamorphosis into a "role."

Torfs' interest in Eisler isn't surprising. She discovered him many years ago as the composer of the score for Kuhle Wampe, the 1932 Slatan Dudow/Bertolt Brecht film, and was impressed by how his music never merely illustrated the narrative, but rather, provided a counterpoint to it. An artist who has long explored the relationship between text and image, in Eisler Torfs found a composer equally interested in language, whose art songs are "masterly miniatures written with a delicacy of touch and an exceedingly refined ear for the rhythms and meanings of a text."5

Torfs often begins a project by exhaustively researching historical documents and literature. After deciding to work with the Hollywood Songbook, she tried to find out how Eisler would have intended this material to be performed. She listened to all of the available recordings. She had a revelation when she found a reissued album with recordings of Eisler songs, including selections from the Hollywood Songbook, by soprano Irmgard Arnold, who was one of Eisler's favorite performers. The end of this album had Hanns Eisler himself singing several songs during a rehearsal session with Arnold. Hearing this convinced Torfs that her assumptions about how to proceed were correct. She was also delighted to discover Arnold, now 85, still lived in Berlin. A soprano star of the Komischer Oper in Berlin from 1950 until 1989, Arnold enthusiastically agreed to participate in the project. She told Torfs in one of their conversations last year, "Eisler did not expect a faithful note-by-note rendition from a singer. What mattered to him was the attitude, the proximity of "epic" music-making to the melody of speech." Arnold was one of the few performers able to sing in accordance with Eislers' slightly paradoxical instructions to be simultaneously "cool, courteous and tender."

Torfs sought out 20 additional performers who, for the most part, are not classically trained, often having backgrounds as actors. She looked for an interpretation at odds with the serious content of some of the songs, such as the ability to inject wit and kindness while singing the darkest of lyrics. "Contradiction" (Widerspruch in German) was one of Eisler's favorite concepts, and he explored it in his directions to singers for the performance of his compositions. Eisler said what he looked for in a singer was, "Someone who knows how to avoid sentimentality, bombast, emotion and stupidity of all kinds, presenting the text well and still really singing... It ought to be someone with a very good voice in the first place, great musicianship, and what I would call 'musical intelligence'. In other words, singing the text in a contradictory way. For instance, when the word 'Frühling' (Spring) comes, the singer should not indicate the season of spring with a melting voice - to put it quite bluntly. ... At any rate, it will be a singer who is not a blockhead. He will sing it well, maybe even with no voice." 6

Most of the songs are very brief, often described as miniatures with a haiku-like intensity. Sung here in the original German (though only one performer is native German), the lyrics were newly translated for this project. The selections range from the most concise, Elegy III: "Every morning, to earn my keep / I go to the market where lies are sold. / Full of hope I mingle between the sellers." to the longest, Tank Battle, which begins its three stanzas with "You, dyer's son from Lech, / who, long ago, used to compete / with me at marbles, / where are you in the dust of army tanks / waltzing beautiful Flanders flat?" Many invoke wit in a more timeless questioning of cruelty, such as The Mask of Evil: "On my wall hangs a Japanese woodcarving, / mask of an angry demon / coated with golden lacquer. / Compassionately I look upon / the swollen forehead veins indicating / what an exertion it is, to be evil." And several address the plight of someone in exile, including Fleeing: "Fleeing from my countrymen / I have now reached Finland. / Friends unknown to me yesterday, / have placed beds for us in clean rooms. / Over the radio I hear the victory reports / from the scum of the earth. / Inquisitively, I look at the map. High up in Lapland, towards the Northern Ice Sea, I can still see a tiny door."

It is interesting to note that Eisler composed the Hollywood Songbook during the period following the United States entry into World War II, when, German immigrants (even those who fled Hitler) were forced to register as "enemy aliens." In a statement Eisler issued upon being forced to leave the United States in 1948, after his interrogations by the House Un-American Activities Committee, he said "A composer knows that music is written by human beings for human beings and that music is a continuation of life, not something separated from it."7 Living through one of history's most tumultuous periods, he aspired to make music that would inspire rather than mollify listeners. Despite his personal tribulations, twice having to depart countries due to political persecution, he retained his optimism and belief in music as a way of initiating reflection.

On a sketch for a forward of this song cycle, Eisler wrote: "In a society that understands and loves such a songbook, life will be lived well and without danger. These songs have been written with such a society in mind." Life without the kind of danger Eisler refers to seems to be moving farther away, rather than closer. But Torfs, in her own searching, brings Eisler's relentless optimism and dark humor to the fore for consideration with the exquisite performances she elicited for this project.

1. Cycle of Trifles, 1998.

2. Literally means "about lying falsehood."

3. Robberechts, Catherine. "Impossible Portraits". In Uncertain Signs / True Stories, Exhibition Catalog, Karlsruhe, 2002.

4. Biographies of the performers can be found in the credits, linked from the bottom left corner of the main screen.

5. Eichler, Jeremy. "A Welcome Tribute to a Lost Composer," The New York Times, July 11, 2003.

6. Quotation by Eisler in Hans Bunge, "Fragen Sie mehr über Brecht." 1971.

7. From a statement Eisler read to reporters at the airport before leaving the United States with his wife, Louise, on March 26, 1948 to go to Vienna via London and Prague. http://eislermusic.com/depart.htm

For more information about the work of Ana Torfs, visit www.anatorfs.com.

Artist

Ana Torfs

Ana Torfs was born in Belgium in 1963. She lives and works in Brussels.